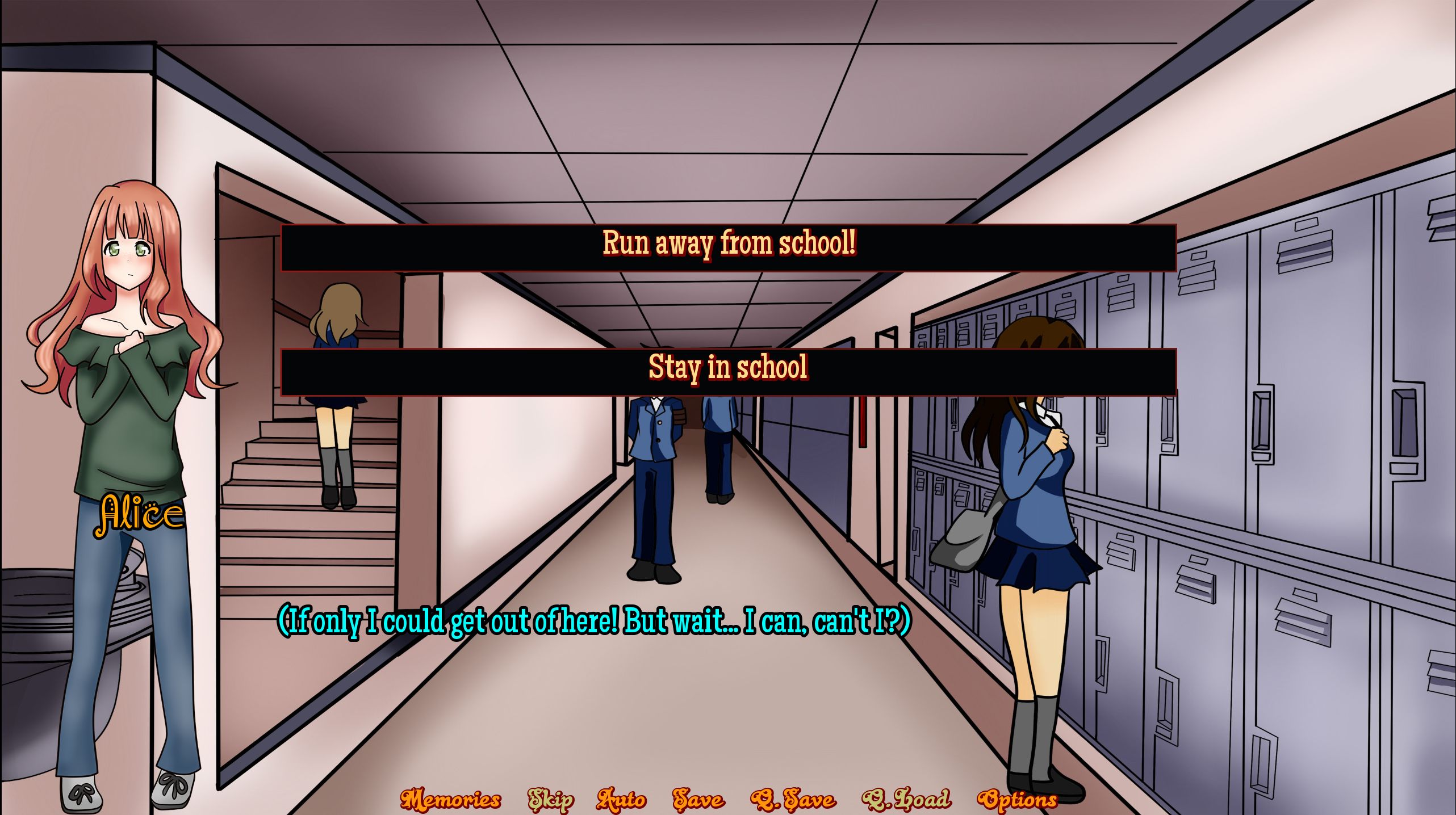

But removed isn’t always the same as gone, and exploring Steam’s deleted items is an adventure through modern gaming history. I spoke to some developers of delisted games to find out more. You can see every game ever delisted from Steam at Steam Tracker which, at the time of writing, has over 3,800 entries, also including retail-only Steam keys and pre-order exclusives. That’s not including the games that have been banned from Steam, some 4,200 of which you can see using madjoki’s Steam Tools. Some regularly-updated series remove older entries as a matter of course. You’ll see a lot of old editions of Football Manager on any index of delisted titles. Other games are quietly shuffled into oblivion by their publishers or drop out of existence when their studio’s new owner has no interest in the original property, or releasing new keys for it. The original Prey from 2006, 2009’s Wolfenstein, and 2010’s Alpha Protocol are all unlikely to see an imminent return, despite their cult status. The Project Cars series is a more recent casualty, taken out of production and off the market by EA. Many removals are for prosaic reasons: a re-release, new edition, remaster, or change of publisher. Generally, they’ll pop up again with a new AppID, although some remasters have seen the original taken off sale, sometimes to the ire of long-time fans. Other times, it can become practically or financially unviable to maintain support for a game; this affects multiplayer games, and those whose single-player experience depends on an always-online authentication service, whether they need it or not. But ageing code and connectivity issues aren’t just for large-scale online service games. Released in 2015 by Dejobaan Games, Elegy For A Dead World is a side-scrolling writing prompt game where the player must explore and describe alien worlds inspired by the poetic works of Keats, Byron and Shelley. Co-developer Popcannibal would go on to release BAFTA-award-winning Kind Words. But the story-sharing feature of Elegy For A Dead World stopped working and the game was removed from sale in January 2022. For some developers, the reasons for a game’s removal are more personal. Indie dev Mia Blaise-Coté’s assessment of the market for her visual novels is frank: “The games were not profitable financially, and I feel like they were never ‘good enough’ for the customers and as commercial products.” She removed all her games from Steam and wiped her name from the developer records of most of them. “At the time, I wanted to leave them behind and not have them associated with me,” she tells me. Later, she’d put her entire games catalogue online at Itch: “At first, I thought about selling them there, but almost nobody was buying copies, so I switched them all for free.” Blaise-Coté’s work has a distinctive style and literary voice, aided by her use of both French and English text, often in parallel, throughout many of her games. But she won’t be coming back to game development. Her last game, 4 Alice Magical Autistic Girls, cost 5K CAD to produce and was a financial loss. She was only able to recoup part of her costs through a final sale before removing the game from Steam. “I feel like that for 4 Alice Magical Autistic Girls to be a commercial success and for me to produce more visual novels, I would have to spend five times the amount of money to create it plus the marketing,” Blaise-Coté says now. The game was praised for its plot, its portrayal of of autism and its fully-voiced French narration by Chloé Guérin, but Blaise-Coté says that its art didn’t stand out compared to other games in an already saturated market, making it difficult to get noticed. “It’s the game that took the most time, energy, and money to produce. I was really hoping it would have worked as a commercial game," she tells me. “While I still love the genre and I would not mind making more, I simply don’t have the motivation and the financial means to do new games.” Blaise-Coté now publishes original stories and fan-fiction, on AO3, including adaptations of her visual novels - some with added explicit content. By contrast, Quentin Lengle had no choice about whether to remove Blade Runner 9732, a free VR experience that he worked for four years to create. Despite Lengle having obtained the go-ahead to release it as a fan work from Warner Bros., the owner of Blade Runner’s intellectual property, a Warner subsidiary named Alcon Entertainmenet filed a copyright takedown. Alcon never responded to Lengle’s efforts to resolve the licensing issue. “The Valve guys were great and friendly,” says Lengle. “They tried to temporise a bit. Like me, they were quite annoyed with this shutdown request coming from Alcon. They knew about my relation with Warner Bros. and they had a copy of my discussion with the LA studio.” But in the end, Valve had to remove Blade Runner 9732’s Steam listing, saying that they faced legal action from Alcon if they don’t comply. Alcon followed up by making copyright claims against all of Lengle’s devblog videos on YouTube. The removal of the game has had little impact on L’Engle’s career - he’s a lead technical artist working on AAA car games at EA, as well as a successful freelance creative director working in 3D animation. But his beautifully crafted VR work, a four-year passion project, has been largely wiped from the public record - though interested parties can still download the build from his personal website. Perhaps the most famous delisting of a game from Steam was that of Devotion by Taiwanese developer Red Candle Games. RPS has covered the ins-and-outs of Devotion’s abrupt removal from Steam after an art asset invoking a comparison between Chinese president Xi Jin-Ping with Winnie the Pooh was found in the game, prompting review-bombing and the forced closure of Devotion’s Chinese publisher. Devotion would not return to any third-party digital storefront, but Red Candle has bounced back from a setback that would have been the end of many independent developers. “The aftermath of the art asset incident brought an immense impact on both Red Candle and our partners,” says Red Candle producer Mr. Yang. “But against all odds, our team managed to re-release Devotion last year on our own storefront. As a result, we felt relieved, as if a heavy weight was lifted from our shoulders. After all, it was a game we worked on for more than two years, with every member devoted to its creation. Having the game re-released on our storefront not only gives many players a chance to experience the game but helps us, the Red Candle team, to move forward as an indie studio.” Small as it is, sales on the the Red Candle E-Shop have been significantly lower than the game’s original Steam launch sales, but an independent sales platform has expanded the team’s options. It was home to a successful crowdfunding campaign for Red Candle’s next game, souls-like metroidvania Nine Sols. Despite the furore surrounding Devotion, Nine Sols’ demo is going great guns on Steam ahead of a scheduled Spring 2023 release date. Steam’s customers, like those of its peers Epic and GOG, generally retain access to the games they’ve bought if they’re taken off sale. And if you can associate a license with your account, you can download the game. I bought an unused old stock copy of Prey (2006) and Steam cheerfully activated and installed it from the CD key - although not all CD keys are also Steam keys. Where a delisted game was free, you can often still add it to your library using the steam://install/ URL followed by the game’s AppID. You’ll most often have success with withdrawn demos and promotional items, such as Platinum’s 8-bit Bayonetta and Sega’s Golden Axed. Like most areas of software preservation, deleted game collecting is a fascinating rabbit hole to delve into. There are subreddits and Steam groups for dedicated collectors of delisted games, some only allowing full membership to those who’ve managed to acquire a sufficient number. Collectors devote themselves to tracking down Steam keys for these rarities, which can be costly. While you might be able to grab a Fable III key for £25, Clive Barker’s Jericho is priced as high as £190 on key-selling sites, and someone’s currently trying to flog Sumo Digital’s Doctor Who: The Adventure Games collection for £300. If collecting delisted games on a Steam account that, per terms & conditions, is only good for the lifetime of its owner (or Steam itself) feels more precarious than hoarding the cardboard game boxes of yesteryear, it’s at least a way of ensuring that, in the immediate term, Steam’s delisted games are not forgotten.

![]()