Yet it’s also not without its flaws, both in how it designs around the limitations of current VR tech, and in the more mundane challenges of crafting single player adventures. The game takes place in City 17, five years prior to the events of Half-Life 2. Gordon Freeman hasn’t been seen since the events at Black Mesa, and so you play instead as a young Alyx Vance, HL2’s deuteragonist. Alyx and her father Eli have been trying to cause trouble for the occupying Combine forces, and their efforts have led Eli to discover the Combine are holding a weapon of unusual power in a protective vault floating above the city. When Eli is captured, Alyx sets off to rescue her father, and to steal the weapon.

This is a game designed for virtual reality through and through, and it makes a good case for the medium’s benefits from the very first moments. VR conveys scale in a way other games cannot, and gazing up at the under-construction Citadel gave me tingles. It also gave me a whole new appreciation for the intimidating size and dexterity of Striders, who clamber across rooftops on needle-sharp legs, like angry chopsticks in search of a dumpling. But to paraphrase my friend Tom, VR is a revolution in control at least as much as it is in immersion. With motion controllers, you can now reach out and touch City 17 - shoving its crates, rummaging around its drawers, and tossing its exploding barrels into the tongues of Barnacles. To help with this, you have the Russells, a pair of gravity gloves which allow you to target objects beyond your reach and flip them towards you. They’re a good example of Valve’s design skill: while flipping and catching quickly becomes second nature, the Russells remain satisfying to use every time, and they solve problems relating to movement and constrained play spaces in home VR setups. They even, elegantly, display your health and ammo on their back surfaces, removing the need for a traditional HUD.

This feels like a natural conclusion to Half-Life 2’s revolution in physics. That game introduced settings like Kleiner’s labs, where players were encouraged to poke around shelves, tinkering with objects and machinery in ways that were unprecedented for the time. HL:A pushes this to the nth degree. You will spend the game doing three main things: shooting enemies, hacking and repairing machinery, and rummaging around in cupboards. As I moved through the city’s factories, distilleries and apartment buildings, I came to think of Alyx Vance as a very hungry contractor. I’d fix some wiring, then go looking in the cupboards for something to eat, only to find nothing but shotgun shells and ammo clips. In fairness, these bullets are extremely useful. You’ll spend as much time in combat during Half-Life: Alyx as in any previous Half-Life game, and many of its iconic enemies return - albeit tweaked in small and clever ways to accommodate virtual reality. There are still multiple kinds of headcrab, for example, and they still leap violently at your head. But they’re newly clumsy: they will land on their backs after each leap, and give you plenty of time to dodge or shoot them. Zombies and Barnacles remain mostly unchanged, while Antlions return with new glowing weak spots that encourage you to pop two of their legs off before you burst them via a body shot.

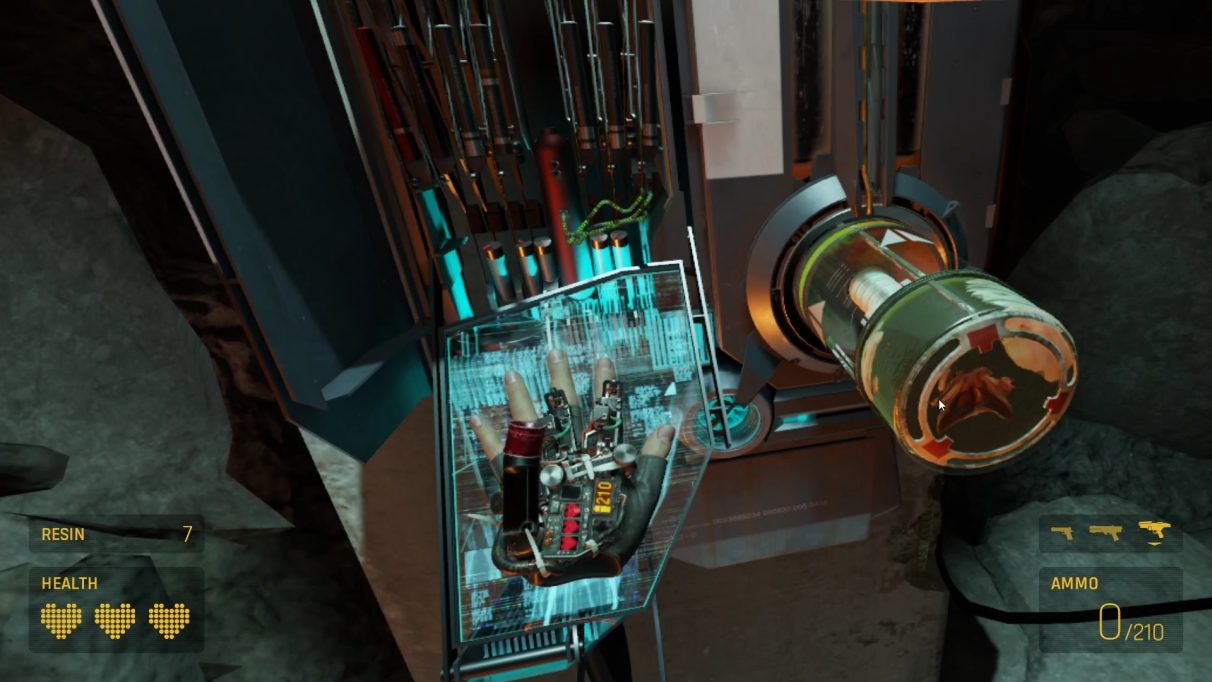

The game has a good line in glowing weak spots generally. Some headcrab types can be killed with a single shot to an exposed heart on their underside, and since they rear back on their hind legs for a second before jumping at you, you’re given the opportunity to crouch down and pop them first. There’s also a new enemy, a sort of speedy electric dog, which can burrow into dead bodies and possess them, but which you can flush loose again by shooting its bright blue prolapses. Aiming a weapon with your motion controllers and pulling off a single, destructive shot feels better than Half-Life’s combat ever has, and HL: Alyx’s aliens provide you with opportunities to do this again and again. I don’t mind at all that the series’ previously vast arsenal has been shrunk to just a handful of tools: a pistol, a shotgun, a Combine submachine gun, and a couple of grenades. That’s because these guns require more thought to operate and maintain than ever before. To reload your pistol, for example, you have to press a controller button to eject the magazine, grab a replacement from your backpack over your shoulder, manually enter it into the weapon, then pull back the slide to chamber a bullet. Doing this while enemies close in on you can be overwhelming, ramping up the already tense combat, and there were many instances where I fumbled shotgun shells to the floor while trying to reload in a hurry. The weapons can be upgraded via Combine machines, using pieces of resin you scavenge during exploration. Upgrades include laser sights, expanded clips, and auto-loaders among others, and as a result even your starting pistol is still essential by the end of the game.

All of this is great, but I’ve not mentioned one of the enemy types yet: the Combine soldiers. In a reversal of almost every other first-person shooter ever made, it’s these most human-like enemies that are the worst to fight. For starters, they’re all bullet sponges. The closest thing they have to a glowing weak point is their heads, or in some instances an explosive gas canister on their back, but even these seem to require multiple shots. They all also have weapons just like your own, which means they can shoot you across large distances, and the speed and quality of their aim transforms the game into a cover shooter. Physically sitting on the floor in order to crouch behind cover feels like a natural action, but, let me tell you, “blind fire” is a myth. There’s a reason why other cover shooters give you extra sensory information via a third-person camera. In Half-Life: Alyx, you have to peek your head out or around cover in order to aim, exposing you to the aim of Combine soldiers, which is uncommonly excellent even on normal difficulty. I found these fights unsatisfying when they were easy, and exhausting when they were hard. Worse, they caused me to rub up against the rougher edges of playing games in VR. Dying because I panicked and dropped my ammo to the floor is exciting, dramatic, a little funny. Dying because I panicked and accidentally holstered my weapon due to the dense face of buttons on a Valve Index controller is frustrating. Dying because I was forced to cower behind an object and my in-game hands snagged on that scenery during an attempt to reload or fire back is infuriating. Worst of all was when I would die as a result of being overwhelmed by all the things I was trying to keep track of, because some of those things were inevitably related to my real-world self: is the headset cable around my leg? Am I nearing the edge of my play space and about to bump into a radiator? In these moments of dying and reloading again and again, I couldn’t help but think about how much easier the fights would be without the awkwardness of VR - which isn’t really the point, I know, in a game that simply would not function at all without VR in so many instances. You may well feel differently, too, if you don’t play at room scale as I did, or if you’re simply better at games.

Thankfully in all other areas of the game, VR feels like a boon, lifting parts of the experience rather than harming them. City 17, for example, is a place I’ve thoroughly explored in Half-Life 2, and found myself exhausted by come the end of Episode 1. Exploring it in VR for the first time was a brand new thrill, however, and this is Valve’s best work in terms of pure artistry. The game’s lighting is particularly gorgeous, filling spaces with atmosphere. The increased fidelity and the new ways to interact with its many physics objects mostly make up for the conceptually lackluster settings. Perhaps I’ve been spoiled by the likes of Dishonored 2, but HL: Alyx’s locales lack a little in diversity, taking you from train yards to factory yards, dilapidated hotels to crumbling apartments. You’ll spend a lot of time around concrete floors and peeling paintwork. Which isn’t to say there aren’t still numerous standout moments within, whether set pieces of cinematic destruction, more visually distinct locations (including an abandoned zoo), or simply gorgeous environment art, such as any moment when you get a glimpse of the enormous Vault hovering above the city. For better and worse, HL: Alyx feels at times like a beat-by-beat recreation of Half-Life 2, with that Vault taking the place of the Citadel. More excitingly, and perhaps more surprisingly, many of the game’s best elements feel like they’re drawn from the original Half-Life. Half-Life 1 was much more of a horror game than its sequel, trapping you inside the B-movie nightmare of a research facility overrun by monsters from another dimension, and eventually sending you to that dimension, Xen.

Half-Life: Alyx embraces horror fully. The majority of the game’s 12-15 hour running time takes place in a part of City 17 known as the ‘Quarantine Zone’, which has been shut off from the rest of the city because it has been infested by Xen’s flora and fauna. Half-Life 2 contained almost no reference to the much-maligned alien dimension, but here walls and floors bulge with imported, fleshy growths. Some are covered with bulbous sacks which burst when you approach, while others snap at your fingers like hungry birds, or exhale an atmosphere of toxic spores. The latter are ingenious, because while you can find gas masks in the world to protect yourself, you can instead choose to cover your mouth with your actual hand, and have the gesture replicated in-game. These spores are present in the game’s standout chapter, in which you’re dropped into an area with videogaming’s most cliché monster design: a big brute that can hear you, but not see you. You have to toss objects to distract him, just as Gordon once did when fighting the original game’s tentacle monster. And although it might be cliché, the scenario escalates with such a perfectly pitched set of no-fucking-way calamities that I was cursing the designers as I played. Picture: me, the hungry contractor, crawling around fixing wires, only to accidentally knock a glass bottle off a shelf. It smashes, and the big brute comes charging towards me like a foreman with a clipboard. I have to put my trembling hand over my mouth to avoid breathing spores, and run off to hide in the corner of the room. It is the most frightened I’ve ever been while playing a game, and yet the absurdity of my real-world actions made it in some ways delightful, too. I was laughing at myself, even in the midst of panic. I loved every moment of this and I don’t like horror games - or horror anything. I am a giant wuss, and prefer my fiction to tell me comforting lies, thanks. What prevented HL: Alyx from scaring the headset off me was its sense of humour, which its characters also use to stave off their own fears. The aforementioned anti-grav gloves, the Russells, are designed by a scientist named Russell, and he’s your in-ear companion, bantering with you throughout the game about what you’re looking at or doing in any given moment. When Alyx enters a dark tunnel with her newly-acquired flashlight, she asks Russell to talk in order to soothe her nerves. The results are funny and, as a result, effective at calming my own feelings of dread.

I also don’t particularly enjoy being an electrician, and yet I enjoyed the surprising amount of time Alyx spends fixing old wiring. You do this using her multitool, a device she invented herself - she suggests to Russell that she could call it “the Alyx” - which allows her to hack Combine terminals and reveal electrical currents running through walls. This involves running it along those walls, working out how to reach the areas the current leads through, and re-routing power to where you need it to go. This is about as Half-Life as it comes - Gordon loved routing power, too. When it comes to hacking ammo boxes, weapon upgrade stations, and trip mines, there are a couple of minigames played via 3D holographic projections. One requires you to move a symbol across the surface of a globe towards a target while avoiding darting red lines, and another requires you to move a dot through hoops before a pursuing red dot catches you. These are simple spatial puzzles, almost like fairground toys, and have no cost for failure. I enjoyed them well enough. Alyx is Half-Life’s first speaking protagonist, and the change comes as a relief, not only because it keeps the fear at bay. The dialogue is great throughout the game, particularly in instances where Alyx asks Russell about what life was like before the Combine took over. It’s also just fun to hear Alyx remark upon the things you discover while exploring, operating as your emotional guide to the world just as she did in previous games.

On your journey, you’ll encounter a handful of other characters, both old and new. A couple of these are a bit Billy Exposition, arriving only to deliver some information about the scenario you’re entering and leaving again when finished. They offer welcome lighthearted respite, but they also harken back to characters such as Half-Life 2’s Odessa Cubbage - who explains how rocket launchers work, then buggers off - in a way that today feels old-fashioned. More promising are a handful of instances where these characters, or others, dynamically comment or react to decisions you’ve made, such as objects you’re carrying or items you’re wearing. Still, I find myself yearning for a Half-Life game that goes further, and learns more from modern linear narrative games such as Firewatch. But mainly I just yearn for more Half-Life, in whatever form Valve wants to deliver it. It was about three hours after reaching the game’s thrilling, won’t-spoil-it, can’t-wait-to-talk-about-it conclusion that a thought occurred to me: for a brief moment I had had a new Half-Life game to play, and now, again, I had not. I hope I don’t have to wait for brain-computer interfaces to exist before the series returns again, because despite a handful of complaints, I still think Valve make the best first-person shooters around.