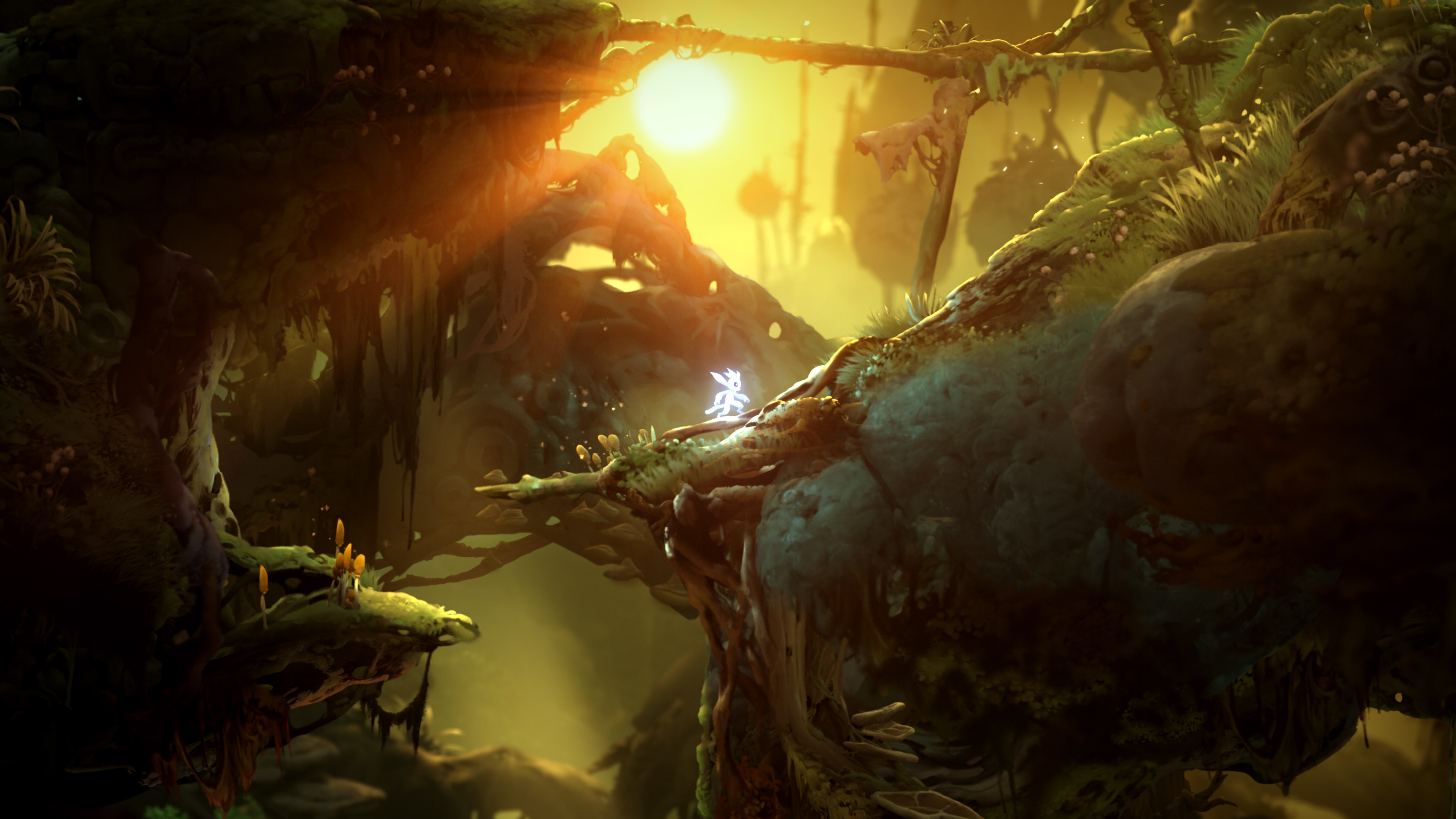

With Ori 2 releasing on March 11, we got to chat to Coker about what makes the new soundtrack, and the game underneath, tick. Turns out it’s not just about playing the hits - although I am dying to hear “the most emphatic” version of the main Ori theme - but showing character psychology through subtle tweaks, and establishing a larger cast of characters without driving ears insane with repetition. And you thought Ori’s job was tough. It all makes more sense if you listen to the soundtrack in question, so why not watch our recent video first - it’s a collection of striking scenes from the first three hours of the game, with only minimal nattering to distract from them. We defy you to watch the opening cutscene or the final chase sequence without the hairs on the back of your neck jump up like an orchestra about to take a bow. This one is going to be a winner.

RPS: The game was revealed with you playing the piano at E3, which I think shows how much music is associated with the game. How did it feel having that put front and center at the reveal? GC: When we first decided to do it like that, I have to be honest all I could think about was ‘my goodness, I hope we don’t screw up’. That really was very live. There was a backing track to fall onto, but all I could think about was if I screw up this is going to be on the internet forever. But it’s obviously a big honour to be put on stage. But my emphasis was if you’re going to put me on stage, let’s not have too much camera on me, because the game looks so good. So they only did it at the beginning and the end - the best of both worlds. I introduce it and then we focus on the visuals for the whole thing. But I think it speaks to the audio visual presentation of the game as a whole. Anyone who played the first game that’s one of the things that jumps to mind. When you’re revealing the game you want to remind people this is the Ori you know and love, except we’ve dressed it up considerably.

RPS: As a composer what are your first steps with a sequel like this? GC: It’s a bigger game and has more characters. That’s the first thing one looks at when approaching the music of a title like this. With the characters, there’s a new baby owl who you meet in the prologue, so it’s immediately a chance to write a new theme. The first game’s soundtrack is very reliant on a single theme, but that’s partially because you’ve only got four characters in the game, and you only spend time with one of them! Whereas this game, you spend more time with different characters: there’s the baby owl, a giant toad, a spider we’ve shown in the trailer… there are a couple of other creatures we haven’t even shown yet. One of the biggest additions is the boss fights, which we didn’t have in the first game. My approach to combat in Blind Forest was to not have combat music for regular moment-to-moment combat where you might fight a monster for three seconds then you aren’t fighting for another three minutes. If you change to combat music every time you fight a monster it becomes jarring and reminds you you’re playing a videogame. Generally speaking, we only use combat music when you have to kill something to progress. That means combat music has more impact when it comes in and then we go really big on music when it’s a big boss fight. It’s about picking the right moments to play the right music. And because this is an open world, everything has to flow seamlessly - there are very few spots that don’t have music at all, because that’s the DNA of the game. So you have to pick your battles about where it can ebb and flow. One of the things I like about the game is that when it’s big it’s really big, and so the epic end of the game is much bigger than anything we have in the first game. But also when it’s quiet, it’s quieter than anything in the first game. So just the range of the soundtrack is much larger.

RPS: You touch on bosses there, and they’re one of reasons the game feels a bit darker from the original. Would you say the score has evolved in a similar way? GC: It is darker. It’s a reflection on the fact that Ori isn’t a kid anyone. He’s done some stuff. He went through quite a ride in Blind Forest and the music reflects that. For example, we have chase sequences in the game again, but where in the first game the chases are a terrifying thing for Ori, these chases sequences are more ‘oh I’m doing this again’. It’s a subtle change in how the music makes you feel. While the boss fights feel like ‘oh my god, I’ve never experienced this before’, so it would be terrifying from Ori’s perspective. My music generally tries to take Ori’s point of view: what is the music that Ori might be thinking about while he’s going through the world. I will say that anyone who played the first game and plays through to the end of this game, there are callbacks to the original soundtrack and everything builds towards the ending. If you did play the original you’ll feel extra rewarded at the end. You kind have got to do that in a sequel, you can’t just ignore the original and that was one of the biggest challenges. When you start out a project like this how do you make the music better? What does ‘better’ even mean? Same with art: what does it mean to make onf of the best looking games ever made ‘better’? And it took us awhile to define that.

RPS: When you’ve written a soundtrack that is instantly beloved - as Ori’s was - does that create a tension between delivering the hits that people expect and wanting to push in new directions? GC: Ori meeting a lot of new characters means I don’t have to rely on Ori’s original theme as much. Take the toad as an example: he has a great character arc, it’s one of my favourite stories in the game. The toad has its own theme you hear in its environment, then when you meet the toad you get it’s theme in its full glory. Then later on when the Toad’s story develops you hear the story in a different way. It gives me more flexibility. With regards to the original theme, I call it the golden bullet. Because it’s such a powerful theme, especially for anyone who played the first game, I’m actually choosing very carefully where to play it. There’s one point in the game where we play the most emphatic version of the theme there’s ever been, but it’s a very specific location where I figured it would be most powerful. If I was to be hyper critical of the first game’s soundtrack I would say it’s too reliant on a single theme. It’s not a problem and it helps set up the second game as it allows me to explore themes, but I have that one to fall back on if I’m ever running into issues. Having more environments and characters in this game allows me to mix up themes which helps the player experience and helps things become less repetitive. Because it’s a bigger game it’s more work, but actually it’s made things somewhat easier in how to use melodies in different areas, because there’s more room for me to do it.

RPS: You mention this big theme that people know and recognise. Do you write your music to be listened to as standalone? There’s a habit in games for music to vanish into the background, do you write for it to work in isolation? GC: Primarily it has got to work with the the game. With strong melodic themes you’ve got to be careful, because if you hear them too much it becomes repetitive. Obviously this comes down to taste and you can’t satisfy everyone, but I’ll always maintain the opinion that if the music is satisfying to listen to and is good - whatever that means! - people are going to be less bothered by it. But if it’s catchy in an annoying way, then yeah, you’re not going to want to listen to it. This game is very helpful with regards to that as you can’t really do a catchy, over-the-top John Williams-style Star Wars melody because that just wouldn’t work. The nature of this game, with its floaty, ethereal atmosphere, is that music is never truly in your face, except when it needs to be. When it isn’t bashing you over the head it actually becomes palatable to listen to over a longer period of time. You can get away with that in a film because it’s a finite experience. You can play the melody really loud. ET is a great example, building to that massive moment the kid takes off on the bicycle and the music gets really big. But that works because it’s a three minute sequence. If you were replaying that sequence over and over again, you’d ask them to turn the music down! In a game like this, which is so big, you can’t make everything memorable. That’s impossible, the brain doesn’t work like that. In a big open world game you want people to take home moments they can remember forever. If you look at Blind Forest pretty much everyone - for good and bad reasons - remembers the water chase sequence because they got an immense feeling of satisfaction when they finished it. Of course we want the moment to moment gameplay to feel awesome, but we also want them to think ‘wow, that fight against the giant spider was incredible’.

RPS: Speaking of chases, they were our favourite moments in the first game, especially how choreographed they felt to the music. How do you create that connection? Do you have the game to play when you’re writing them? GC: I’m heavily involved in the game early on in development when there’s no art or anything. I know how it feels early on. I remember when I first did the chase sequences I did typical action music. Very intense. It wasn’t really working and all I did was add the main theme on top and there was the answer. In this game my approach differs depending on the situation. In some of the boss fights you’re fighting the boss, then there’s a chase sequence and then another part of the boss fight. So it’s combat, chase, combat. In phase one you might have the melody for the spider, then you’ll have the typical chase music which is a transitional piece, and then the final part you’re winning the fight so more optimistic music plays. And maybe Ori’s theme plays to reflect the fact you’re doing well. There are all kinds of subtle changes in the music that reflect how you are doing as a player and to reinforce the things you are doing. Even in puzzle rooms, the music changes in a subtle way - there’s lots of little examples throughout the game that we couldn’t do in the first one because we didn’t have the technical expertise. But this time we’ve got more resources and the technology to get more music to play in the right situations. This is reflected in the length of the soundtrack - I’ve literally just finished cutting the soundtrack album. It’s 186 minutes, as opposed to 92 in the first game. And I made cuts to that 186 minutes. But it’s reflective of what every player who finishes the game will experience with it.