That would be fine, except for the way splendid turn-based Kaiju murder has seeped into my daily life. If we were face to face right now, there is a good chance part of my brain would be thinking about how I could best manoeuvre you into an imaginary pit. I’m very sorry. I cannot stop. I haven’t even played for a couple of days, but the visions persist. Yesterday someone at the pub had their chair perched in front of a step, which meant I couldn’t follow the conversation because I was too busy thinking about how he’d tumble if I launched a rock behind him. It would have been such a sweet shot, you see, with the bonus impact of knocking a table backwards and doing one point of damage to the strangers sat some distance away.

I’m experiencing a potent version of the Tetris effect, a psychological phenomenon not to be confused with the modern, fancy version of Tetris that got named after it. This is when a game elbows its way into your unrelated thoughts, traditionally manifesting in the sight of falling tetrominos or a desire to reorganise supermarket shelves. Study of the effect has since been broadened into “game transfer phenomena”, pioneered by Ortiz de Gortari. Mark Griffiths is also involved, i.e that bloke who everyone with a Psychology A level remembers as ’that guy who did the gambling studies’. Gortari’s site makes for interesting reading. I’m delighted with the results table from this post, revealing that 69% of sampled Turkish videogame players have “unintentionally sang, shouted or said something” from a game. I haven’t yet started yelling about our need to abandon this timeline before giant insects consume the planet, but the week is young.

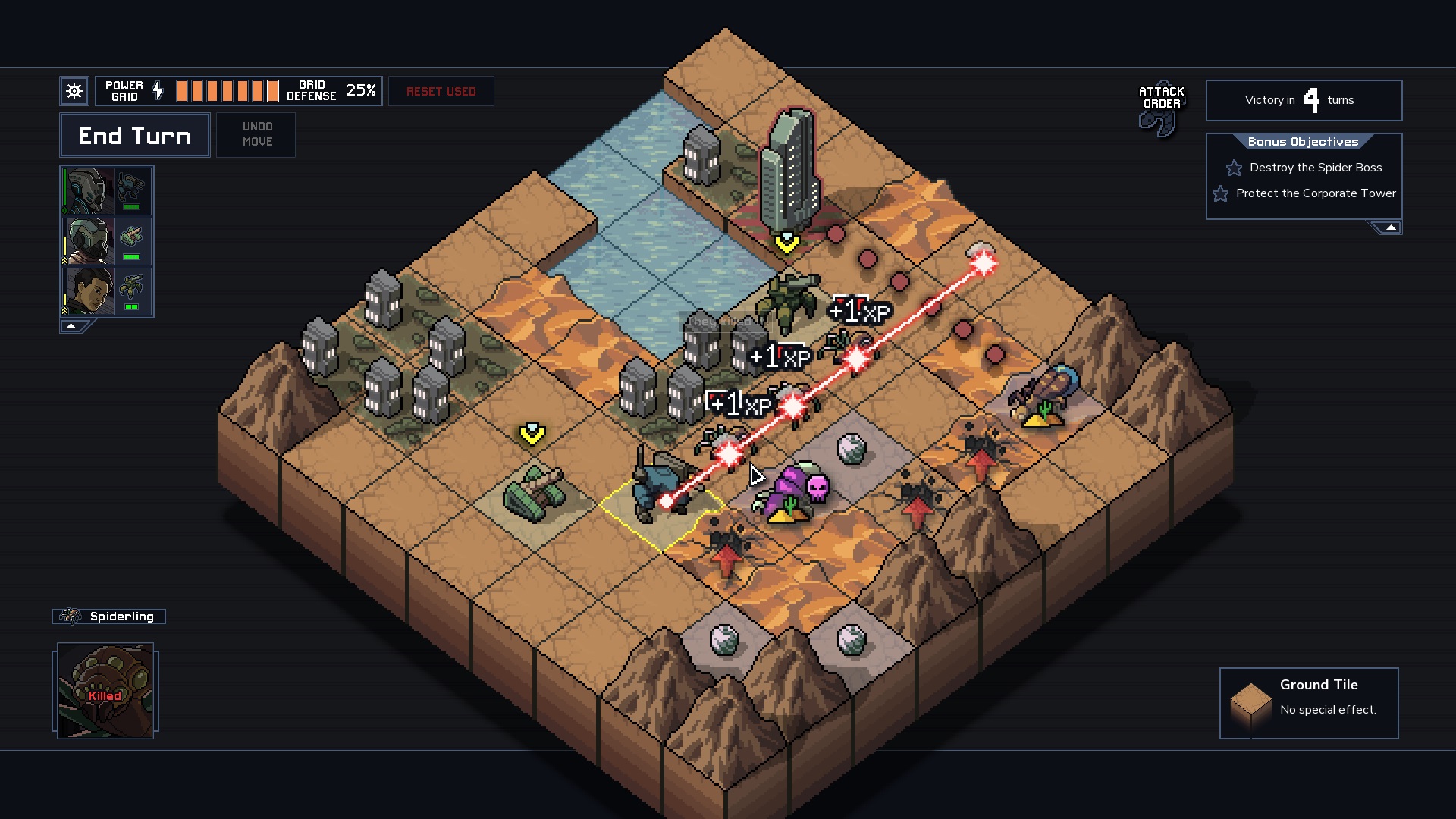

Much of her writing is behind those paywalls that plague academia, so I’m not sure what Gortari would say about why GTP has hit me so hard with Into The Breach. My guess is that it has to do with constant pattern searching, and the way I’ve trained my eyes to crave opportunities for efficient bug splatting. The problem is that the patterns Breach has trained me to look for include ‘X thing being next to Y thing’. That’s because monsters and mechs take damage if you push them into each other - or into structures. Over the hols I met up with a friend I hardly ever get to see, and couldn’t stop fantasising about shoving him into a pillar. Gently, like. That’s a small taste of the phenomenon’s dark side, which the Metro once seized on with the panicked headline “Gamers can’t tell real-world from fantasy”. Gortari and Griffiths rebuffed that, restating that the study in question didn’t provide much evidence for people being unable to distinguish life from game. Nevertheless, potential negatives are part of why they’re interested. This primer mentions how GTP can impair performance, and possibly lead people to approaching hazardous tasks or objects due to a perceived lack of risk.

That sounds outlandish, as if someone is going to stand in the way of a combine harvester while believing they can punch through it or something. That said, such scenarios aren’t a million miles from my experience. I once recklessly ate a pizza with precariously balanced pepperoni on it, because I’d just been playing loads of Oblivion and part of me thought I could quickload if any wound up in my lap. This Breaching problem has become more annoying than entertaining, but I can’t find any advice about dealing with it other than “play less”. The psychologists have failed me. To get rid of the actual Tetris effect I once imagined the tetrominos shattering, but my intrusions from the Breach always involve physical people. I don’t want to pile on imaginary shattering to all the imaginary shoving. That would be rude. I turn to you then, reader, for help. And if you don’t have any advice, at least tell me about your own experiences with GTP. I know I’m not the only one who’s broken.