Alas though, citizens. I come to bury Praetorians, not to praise it. Before the burial, however, since even a ghostly Roman is nothing without their honour, I will begin with at least some praise. Praetorians was a wargamer’s wargame. Its 24 campaign missions were varied and creatively designed, and it had an impressively deep set of tactical considerations. Terrain elevation mattered. Formations mattered. Proper scouting was essential. And the “rock paper scissors” principle common to military strategy games, with each unit being strong against some units and weak against others, was masterfully deployed. Leave the wrong kind of unit to face an opposing force, and more often than not, it would be wiped out without managing to inflict any casualties of its own.

Praetorians was not one of those RTS games where victory hinged on the ability to work out which unit to spam in each mission. Oh no, citizen: it required constant situational analysis of what unit types to put where, what instructions to give them, and how best to get them to support each other when the stercus hit the flabellum. All this put it far beyond the plebeian masses of the late-90s/early-2000s RTS boom, where winning was all too often a case of lumping together as many units as possible, and steamrollering them across the map. In fact, Praetorians could be downright brutal. Because not only did it require relentless and careful planning, if you got any of it wrong, or forgot elements, the game would batter you like a quinquereme’s Celeusta seeing to an idle rower. Troops could not withdraw once committed to melee combat, meaning that fights - as in reality - often became almost uncontrollable once the enemy was in range. What’s more, vulnerable units left open to attack during the mayhem - a druid exposed to horsemen, for example - would not just take a little extra damage before scurrying away, but would be trapped in place by their attackers, and near-instantly sent to join my social circle. And woe betide the player who didn’t thoroughly scout ahead before doing anything. Marching troops towards objectives without painstakingly scouting the road ahead for ambushes was, unless you were extremely lucky, a recipe for certain trucidation. Praetorians was harsh. And yet, like all Roman justice, it was also fair.

“But Ghoastus!” you proclaim, from the auditorium of this digital amphitheatre, “why are you using the past tense, o lemur?” Well, citizen: because this is a eulogy for a game that was fairly good, seventeen years ago. And as for the remaster which came out last week? Well, it’s exactly the same game. Yes, it has been transplanted to the Unreal engine, and has been granted better textures, a higher resolution, and a few minor changes to controls and UI. But beyond that, it is an exacting copy of the Praetorians that was released in 2003. And here we get to the business of burial. Because honestly, it should have stayed there. I am the last person, clearly, to argue against the raising of the dead. Indeed, I’d argue there’s nothing wrong with a bit of reviving here and there. Just two months ago, Age of Empires 2 came back to life after two whole decades, as a Definitive Edition. And I was absolutely thrilled by it, for - coincidentally - the exact same reasons Nate outlined in his review. Yes, a large part of this was all the new content added for the re-release. Even without that, though, AoE2 was a good choice for a remaster because its basic model of play hasn’t really been superceded since. Along with Starcraft and Red Alert 2, and whatever other game you’ll no doubt insist gets a fourth place in this triumvirate, it was the high water mark for 2D, isometric-ish strategy games with individual unit control and resource-gathering/economic elements. Praetorians, by contrast, was a low water mark for the strategy games to come. It was presented in 3D, its resource management elements had been stripped to a minimum in order to focus on tactical combat, and it used multiple-person detachments as its base level of unit, rather than individual, scurrying mans. And alas, all of these things ended up being done better, several times, by other games.

Let’s be candid: a huge amount of what appeals about Praetorians was completely left in the dust by the Total War series. While Shogun was actually first to the table in 2000, Creative Assembly went on tackle Rome themselves in 2004, just a year after Praetorians. And more crucially, they continued to iterate their formula ten more times in the decade and a half that has since past. However kind one’s heart, then, there is simply no way to go back to Praetorians’ take on generalship after all these years of Total War, and still find it satisfying. This poor relic was, inevitably, only ever going to feel like Partial War. Some technical examples: the camera’s default zoom is far too close to the ground, and it only has one other viewpoint, which is slightly closer in, and tilted awkwardly upwards. The camera cannot be rotated at all. You can change the direction units are facing, but not the width of their formation. The AI, for all that the game’s innate harshness diminishes its importance, is still a 2003 AI. Time, crucially, cannot be slowed down in fights. Where it becomes really obvious how far things have moved on, however, is - perhaps ironically - in the way the game looks, and the impact that has on the feel of play. All the textures might be better now, and so might the engine - but the models built into it, and the way they interact with each other, feel extraordinarily dated. You can paint a load of knackered old bulldogs any colour you like, citizen, but they won’t turn into greyhounds.

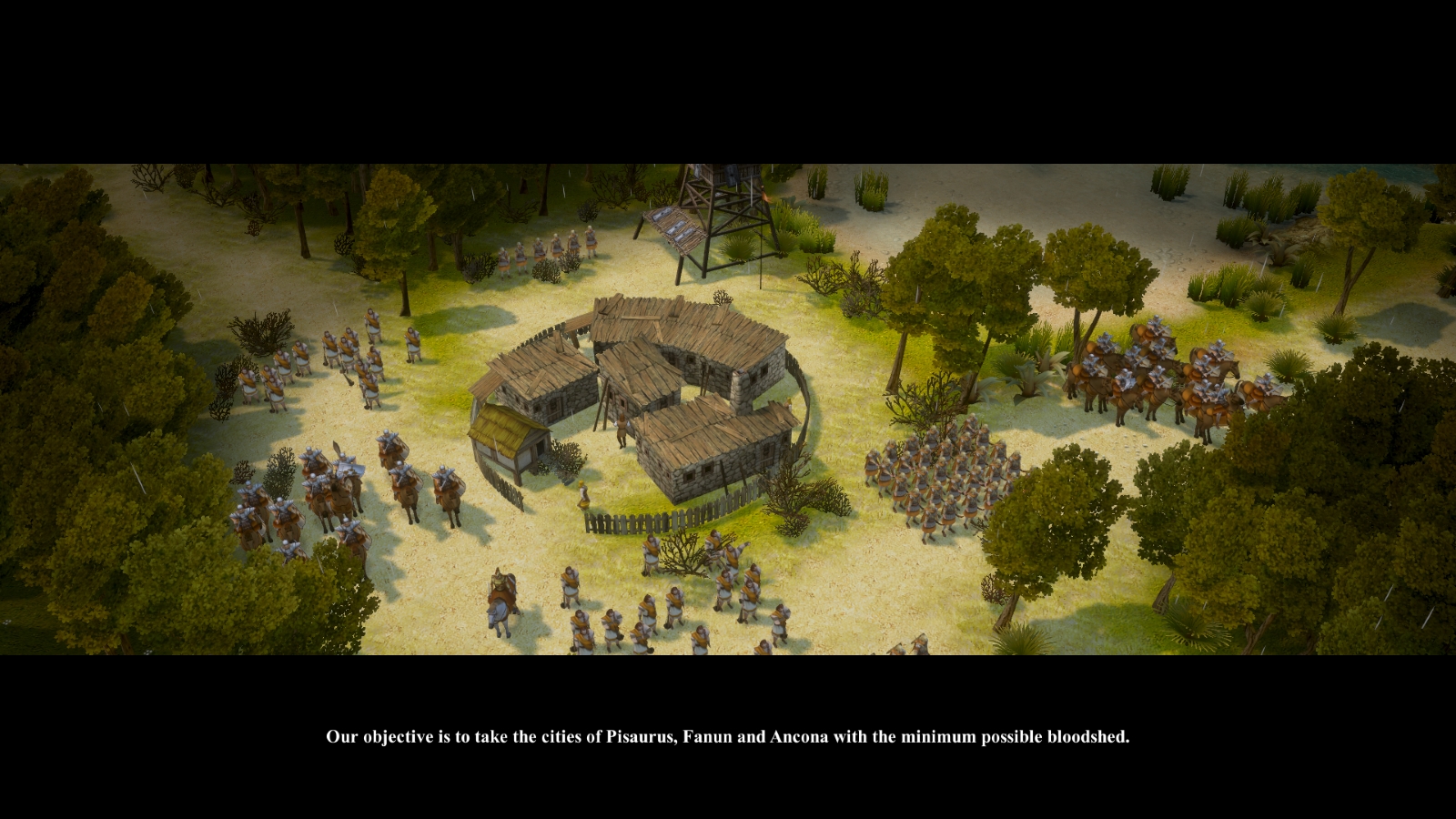

In a development I found strangely relatable on a personal level, Praetorians’ troopers were pronouncedly… spectral. Units of legionaries drifted over the map as if they weren’t touching the ground, arms and legs pumping mechanically in animations which, while asynchronous, made it clear how identical ever soldier was. And not only did they not stick to roads, they straight-up wafted through trees - Eheu! Pleasingly spectral though this was, it was no clipping error: it was just how the game world was built, and it would look silly in any resolution. It’s not just trees, either. Units move through each other just as ghoastily as they slip through the scenery, and through their opponents too. When two lots of troops collide, they just sort of… drift into the same space, before each trooper is drawn randomly towards a partner like panicked teens at a school disco. It doesn’t feel like a fight - it feels like two abstract blobs occupying a single point until one is declared the victor, and the other becomes a series of badly drawn skeletons.

Wooly as the criticism might sound, all of this matters a lot in a game whose strengths are gathered under the idea of tactical realism. None of it feels compelling, or - to use a word made dreadful by overuse, I know - immersive. There’s none of the solidity and inertia you find in Total War, where every regiment feels composed of tiny, heavy little ants with their own hopes and dreams and gladii. What’s more, units have a maddening tendency to do their own thing if not constantly bullied into accordance with your will, and will get themselves slaughtered in a heartbeat if you don’t constantly babysit them. Forget to scout, forget to set formations, forget anything, in fact, and you’ll end up with an army of ghoastuses. The sheer work involved in preparing for a successful attack robs the game of any pace when you’re on the offensive. And when the mission calls for defence, the pacing swings to the other end of the scale, throwing you into a frenzy of orders where a single forgotten command will make the whole edifice collapse.

Now some of this grumbling about micromanagement might sound like it’s verging into a cry of ludens nimis difficilosis mihi! (that’s Roman for “it’s too hard”). And indeed, as I mentioned at the start of the review, Praetorians is hard, but that’s not the problem here. The problem is, it’s the kind of hard you can only begin to overcome by spending so long playing the game that you develop a deep-rooted instinct for the rhythm of a fight - the buttons you need to remember to press, on which units, every few seconds, if you don’t want to be massacred. And yes, when it comes to this sort of thing, practice makes perfect. But speaking frankly, who would want to practice, when the end result is just mastery of a game that was pretty good, seventeen years ago? You could have a lot more fun learning Total War.

But what about those who are already well accustomed to the demands of Praetorians, having the formation-switches and unit ability timings burned into their muscle memories during the halcyon days of the early 2000s? Well! They’ll find… the exact same game! But in higher resolution. And with the multiplayer servers switched back on. And for £14, rather than £4. Is the higher resolution worth ten denarii, citizen? I wish I could say so. Praetorians HD Remaster looks better than its predecessor, but honestly, still looks like a mobile game I’d find in a promoted tweet, alongside a vague imperative like “defend your empire!”. I like the weather effects - the germanic rain, in particular, is very moody - but I’ve been watching old footage of the original, and they’re unchanged from that. The same goes for the much-less-enjoyable voice acting. And the repetitive music. And the video cutscenes, which are pure early-2000s CGI, to the point where every Roman looks like a sad, waxy-skinned mannequin from a struggling local museum. I look upon their doughy faces, trapped in a resolution they were never designed for, and I feel nothing but pity for my fellow relics. These Romans, citizen, were best off not being resurrected.