Rover Mechanic Simulator imagines a reality in which humanity has colonised the farthest edges of solar system, our species’ reach extending to the very worlds our ancestors once gazed up at and dreamt of driving a little solar powered car around on. In this brave new frontier of boundless opportunity, you are the guy whose job it is to stay inside the Martian base and tighten up the loose bolts on the machines that come to you for repairs. You don’t get a window, but you are allowed to listen to the radio as long as it doesn’t distract you from the task at hand. There are five stations in the future, one of which is dedicated to electro-swing, which suggests you’ve ended up on a horrifying alternate timeline in which Caravan Palace went mainstream rather than remained a fun novelty band that we should probably try to move on from rather than base our personalities and wardrobe around.

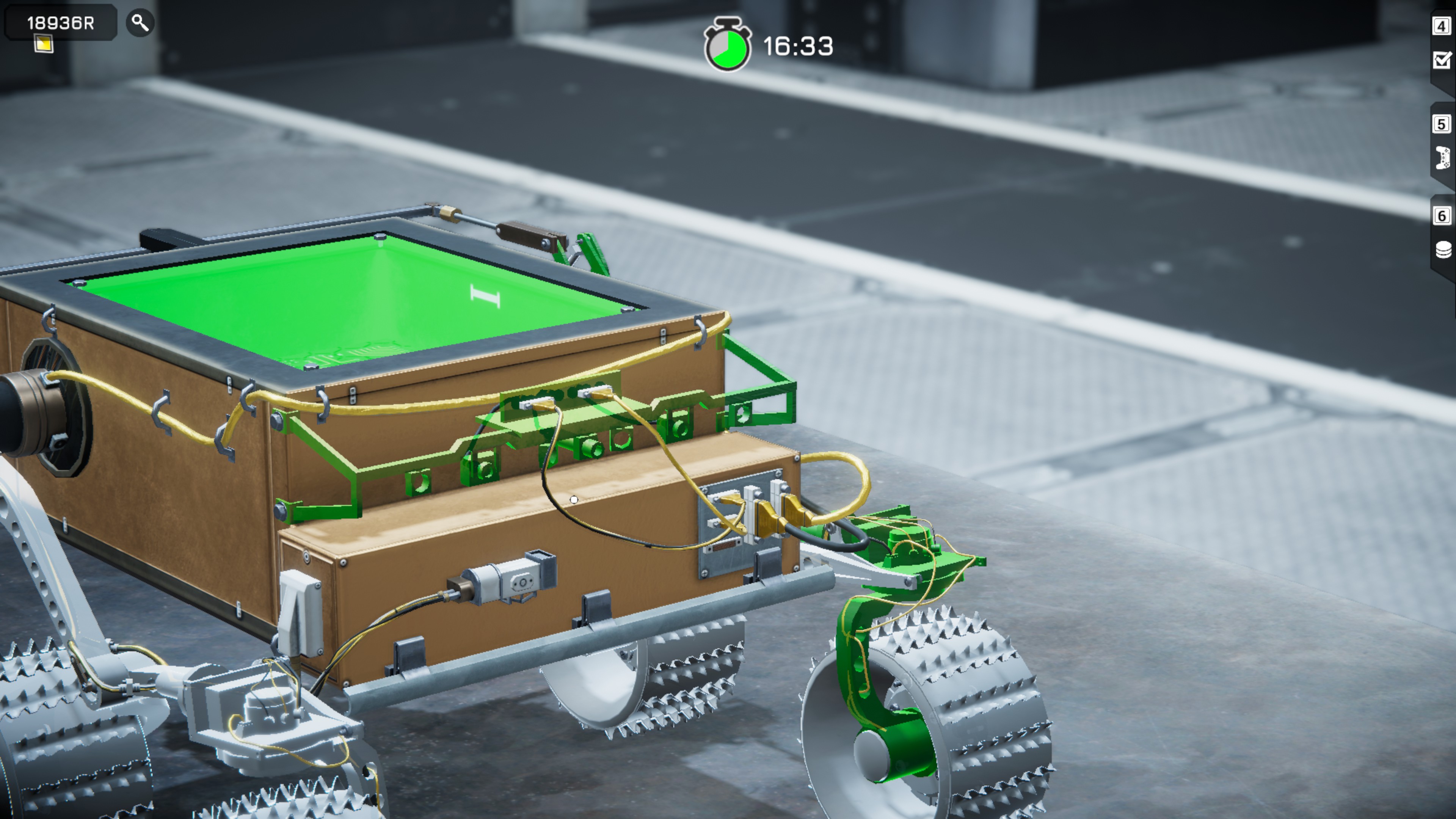

So, sick rovers arrive in your space garage on the back of a space lorry. You use a space crane to lift the rover on to a special operating table for robots, where you can cast your mouse cursor over them to check for faults and space muck. Despite being set in a technologically advanced future in which we’ve arrived on Mars, the rovers you’re working on are distinctly turn-of-the-century, the all-stars of the red planet. We’re talking about Sojourner and Opportunity (though not it’s identical twin, Spirit, which is presumably still hard at work elsewhere on the planet’s surface). For space nerds, poking about meticulous recreations of this famous pair of robots is way more thrilling than popping the hood of a – if you’ll allow me to alt-tab away for a moment to Google the name of a car – a god damned Saab. For one, they’re much, much smaller than you’d expect. Here I thought rovers were massive, able to crush you underneath their giant barrel-sized wheels, but Sojourner is a shoebox with a bunch of cameras sellotaped to it. Opportunity is about as big as a medium-sized dog. These are tiny boys, on a brave space mission to snap pictures of Martian rocks.

Repairs are carried out by correctly identifying broken components, and then dismantling those parts until you can remove the affected bit and swap it out for a freshly 3D-printed replacement. Presumably this sort of advanced mechanical engineering requires at least a couple of days’ training in the real world, but in this simplified simulation there’s no real skill involved in disassembling and reassembling the rovers. Rather the process is a zen-like series of clicking and holding down the mouse button over cover plates and connectors in a prescribed order, from which it’s not possible to deviate. You can’t take a wrong turn and attach a boom arm to a wheel strut. You can’t accidentally bolt the camera module in upside-down and trick NASA into thinking all of Mars has flipped over. Repairing rovers is about as mentally taxing as colouring in, and I think that’s why I enjoy it so much. Instead, a sense of challenge is created in other ways. With some jobs you can promise the client a premium service, which usually means gambling on whether or not you can finish the repair within a set time limit. New parts take time for the 3D printer to produce, so nailing the time limit on more difficult jobs demands that you assess which bits you might need ahead of time. More complex orders have you taking dismantled parts to a workbench to be dismantled ever further, or soldering circuit boards. All of it is just endless clicking accompanied by deeply satisfying animations of parts coming away.

Sometimes clients will only offer a vague description of what’s gone awry with their machine, unhelpful things like “it keeps turning in circles” or “whoops, we crashed it into a big rock”. These ignorant customers made some sense in Car Mechanic Simulator, where it was plausible that somebody wouldn’t know what brake fluid is, but here it suggests a worrying lack of education on the part of space scientists who should probably at least know the names of all the parts of the rover. In any case, vague repair orders require that you first investigate where the problem might lie, sleuthing around the damaged rover like a space Sherlock in search of clues. A rover that only goes in circles is likely to have a dodgy wheel, for instance, so you cast your cursor over each one in turn until you spy a rotten bearing or a wonky axle. Sometimes seemingly simple jobs turn into more difficult ones as the scale of the damage becomes more apparent. A future update should include the option to take a long drag on a space cigarette and say, “there’s your problem right there mate, I’m afraid this whole thing is going to have to come out”.

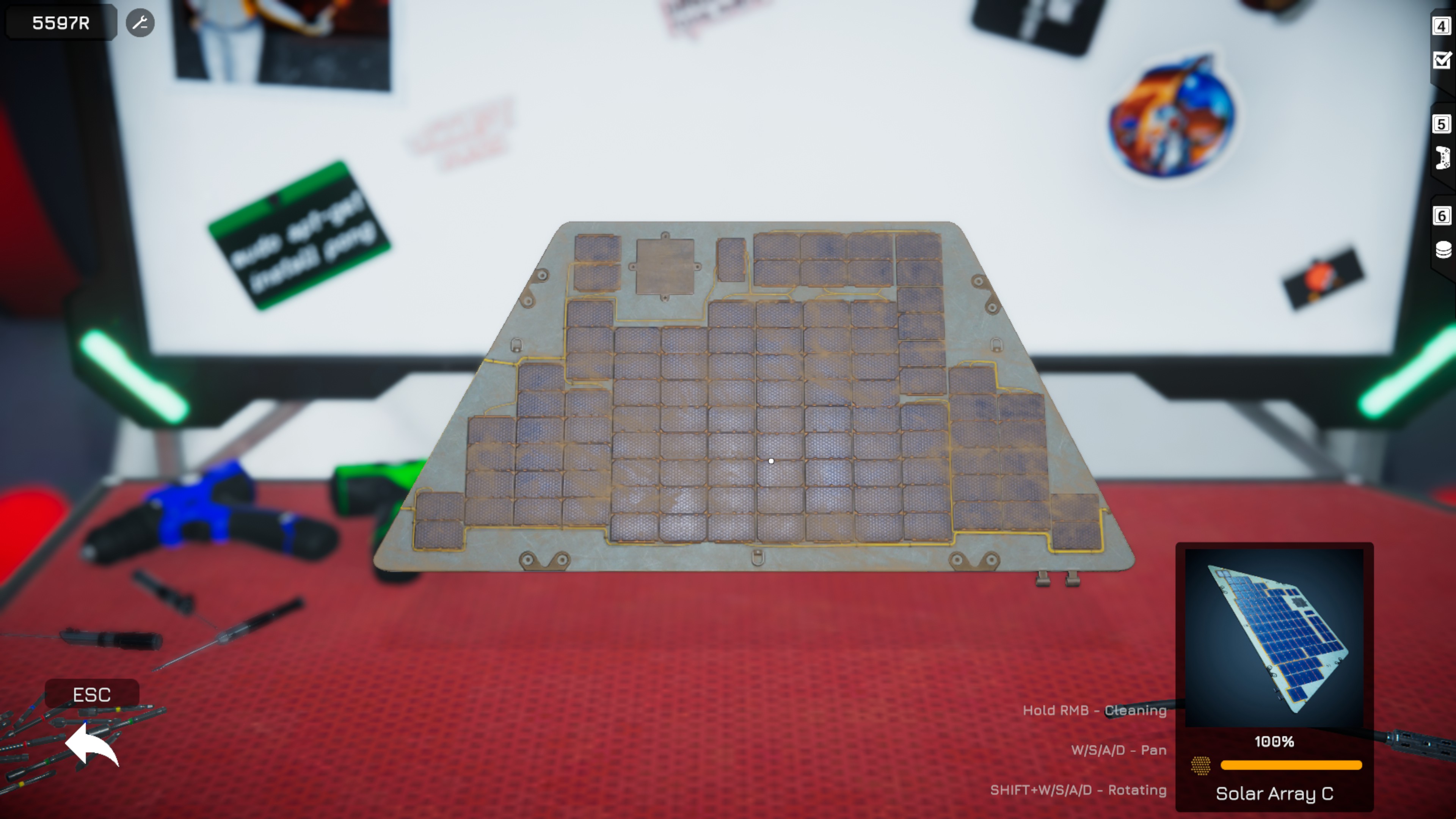

The early access version of Rover Mechanic Simulator features a paltry two rovers, which is fine for a few hours of escapism. Familiarity with the rover’s parts only makes the experience of repairing them even more meditative, more personal. The pancam mast assembly of Opportunity becomes an old friend, the solar array of Sojourner a trusted confidant, your only company in the vast Martian warehouse where you work. Rover Mechanic Simulator is everything I need right now: mindless, barely interactive busywork in a windowless metal box in space, totally alone, where emails can’t get me.